With tools like Wireshark, it's possible to compile TCP streams and recreate image files using the raw captured data. In secured environments, operating systems may be configured to use custom certificates, which make it possible for network administrators to decrypt data going to and a from devices on the network. The usage of images to conceal payloads can make it difficult for sysadmins monitoring traffic to identify the activity as malicious or suspicious. These kinds of firewalls make it difficult for an attacker using simple TCP connections established with Netcat to persist on the compromised device or covertly map the network. With commercial software like Fortinet's FortiGate firewall, each packet can be thoroughly dissected for analysis. With software like pfSense, every domain and IP address visited by each device on the network is logged. In highly secure environments, however, where every domain is logged by firewall software, it may be beneficial to conceal the contents and origin of the payload. In most scenarios, hiding a payload inside an image file isn't required. Also, stagers can be quite small, only ~100 characters long, making them quicker to execute with a USB Rubber Ducky or MouseJack attack, for example. So, why have a stager at all if the attacker is already in a position to execute code on the target MacBook? Well, primarily, varying degrees of active evasion. Don't Miss: How to Bypass Mojave's Elevated Privileges Prompt.The stager is designed to download the image and execute the embedded payload, while the payload is the final bit of code (embedded in the picture) designed to perform one or more commands. The stager and payload are two different aspects of the attack. Instead, the command will be hidden in the metadata of the image and used as a payload delivery system. That's a different kind of macOS attack, something we've covered in another article.

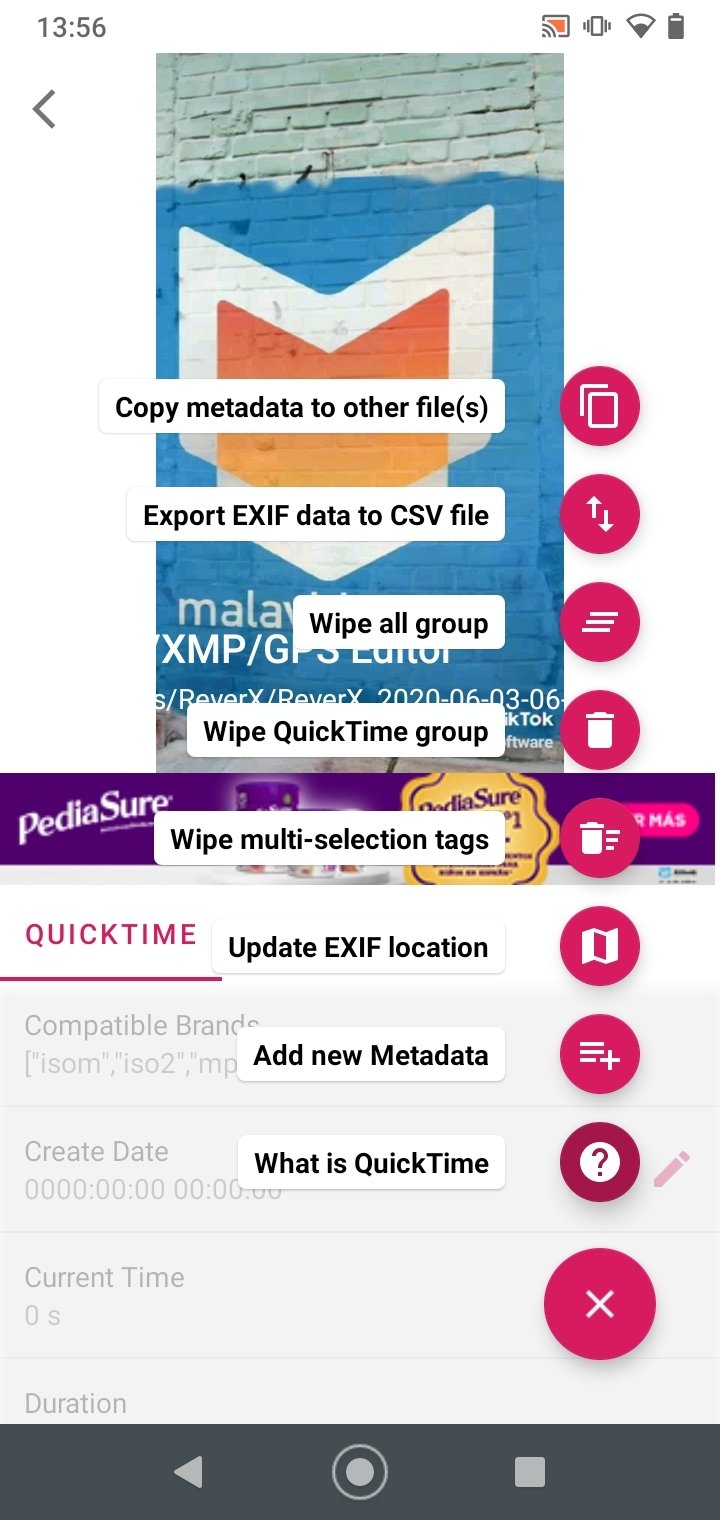

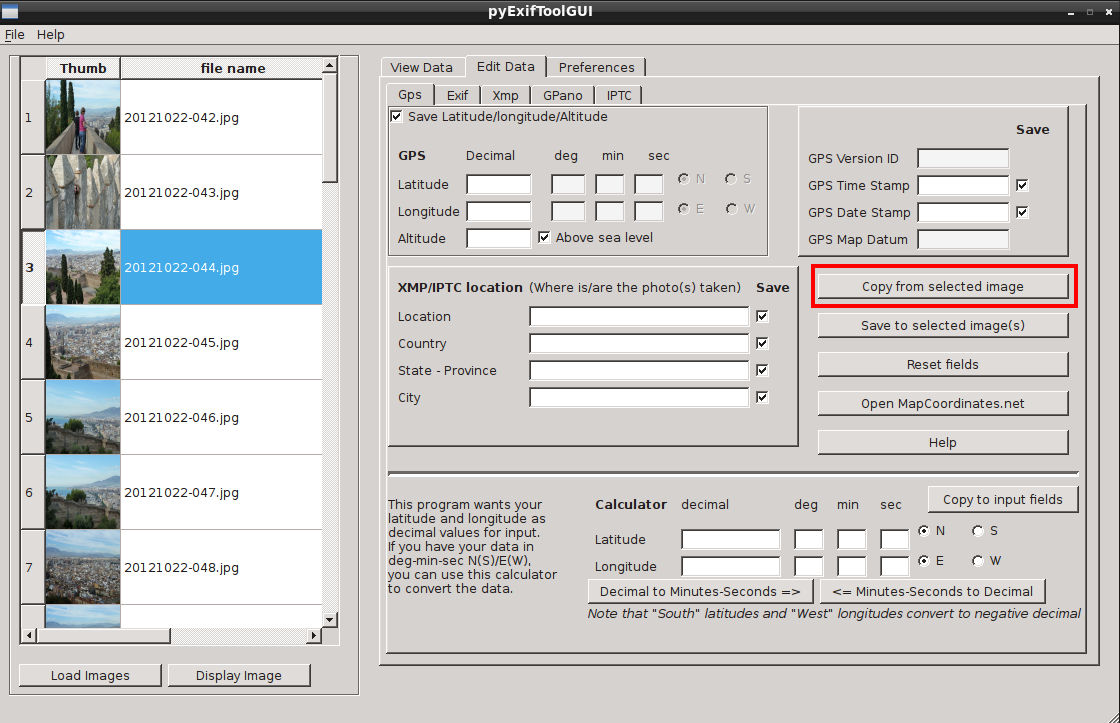

To be clear, double-clicking the image file will not cause the embedded command to execute. A stager will then be created to download the image, extract the metadata, and execute the embedded command. The attacker would host the malicious image on a public website like Flickr, making it accessible for anyone to download. In this attack scenario, a malicious command will be embedded directly into the EXIF metadata of an image file.

In addition to obfuscating the true nature of an attack, this technique can be used to evade network firewalls as well as vigilant sysadmins. Complex shell scripts can be implanted into photo metadata and later used to exploit a MacBook.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)